Deploying and Scaling Microservices

with Kubernetes

Allez-y doucement avec le WiFi!

N'utilisez pas votre hotspot.

Ne chargez pas de vidéos, ne téléchargez pas de gros fichiers pendant la formation.

djalal, Nanterre, 13 sept.

Présentations

Bonjour, je suis:

- 👨🏾🎓 djalal (@enlamp, ENLAMP)

Cet atelier se déroulera de 9h à 17h.

La pause déjeuner se fera entre 12h et 13h30.

(avec 2 pauses café à 10h30 et 15h!)

N'hésitez pas à m'interrompre pour vos questions, à n'importe quel moment.

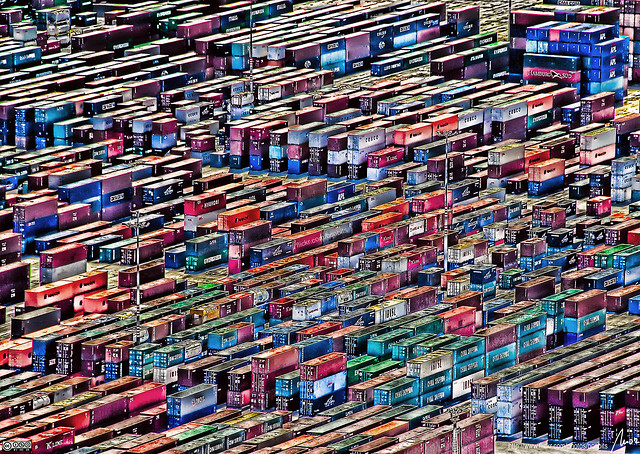

Surtout quand vous verrez des photos de conteneurs en plein écran!

Vos réactions en direct, questions, demande d'aide

sur https://tinyurl.com/docker-w-djalal

A brief introduction

This was initially written by Jérôme Petazzoni to support in-person, instructor-led workshops and tutorials

Credit is also due to multiple contributors — thank you!

You can also follow along on your own, at your own pace

We included as much information as possible in these slides

We recommend having a mentor to help you ...

... Or be comfortable spending some time reading the Kubernetes documentation ...

... And looking for answers on StackOverflow and other outlets

À propos de ces diapositives

Tout le contenu est disponible dans un dépôt public Github:

Vous pouvez obtenir une version à jour de ces diapos ici:

https://container.training/ (anglais) ou https://docker.djal.al/ (français)

À propos de ces diapositives

Tout le contenu est disponible dans un dépôt public Github:

Vous pouvez obtenir une version à jour de ces diapos ici:

https://container.training/ (anglais) ou https://docker.djal.al/ (français)

- Coquilles? Erreurs? Questions? N'hésitez pas à passer la souris en bas de diapo...

👇 Essayez! Le code source sera affiché et vous pourrez l'ouvrir dans Github pour le consulter et le corriger.

Détails supplémentaires

Cette diapo a une petite loupe dans le coin en haut à gauche.

Cette loupe signifie que ces diapos apportent des détails supplémentaires.

Vous pouvez les zapper si:

vous êtes pressé(e);

vous êtes tout nouveau et vous craignez la surcharge cognitive;

vous ne souhaitez que l'essentiel des informations.

Vous pourrez toujours y revenir une autre fois, ils vous attendront ici ☺

Chapitre 1

(auto-generated TOC)

Chapitre 2

(auto-generated TOC)

Chapitre 4

(auto-generated TOC)

Chapitre 5

(auto-generated TOC)

Chapitre 6

(auto-generated TOC)

Chapitre 8

(auto-generated TOC)

Pre-requis

(automatically generated title slide)

Pre-requis

Être à l'aise avec la ligne de commande UNIX

se déplacer à travers les dossiers

modifier des fichiers

un petit peu de bash-fu (variables d'environnement, boucles)

Un peu de savoir-faire sur Docker

docker run,docker ps,docker buildidéalement, vous savez comment écrire un Dockerfile et le générer.

(même si c'est une ligneFROMet une paire de commandesRUN)

C'est totalement autorisé de ne pas être un expert Docker!

Raconte moi et j'oublie.

Apprends-moi et je me souviens.

Implique moi et j'apprends.

Attribué par erreur à Benjamin Franklin

(Plus probablement inspiré du philosophe chinois confucianiste Xunzi)

Sections pratiques

Cet atelier est entièrement pratique

Nous allons construire, livrer et exécuter des conteneurs!

Vous être invité(e) à reproduire toutes les démos

Les sections "pratique" sont clairement identifiées, via le rectangle gris ci-dessous

C'est le genre de trucs que vous êtes censé faire!

Allez à http://container.training/ pour voir ces diapos

Joignez-vous au salon de chat: In person!

Vous avez votre cluster de VMs dans le cloud

Chaque personne aura son cluster privé de VMs dans le cloud (partagé avec personne d'autre)

Les VMs resterons allumées toute la durée de la formation

Vous devez avoir une petite carte avec identifiant+mot de passe+adresses IP

Vous pouvez automatiquement SSH d'une VM à une autre

Les serveurs ont des alias:

node1,node2, etc.

Pourquoi ne pas lancer nos conteneurs en local?

Installer cet outillage peut être difficile sur certaines machines

(CPU ou OS à 32bits... Portables sans accès admin, etc.)

Toute l'équipe a téléchargé ces images de conteneurs depuis le WiFi!

... et tout s'est bien passé (litéralement personne)Tout ce dont vous avez besoin est un ordinateur (ou même une tablette), avec:

une connexion internet

un navigateur web

un client SSH

Clients SSH

Sur Linux, OS X, FreeBSD... vous être sûrement déjà prêt(e)

Sur Windows, récupérez un de ces logiciels:

- putty

- Microsoft Win32 OpenSSH

- Git BASH

- MobaXterm

Sur Android, JuiceSSH (Play Store) marche plutôt pas mal.

Petit bonus pour: Mosh en lieu et place de SSH, si votre connexion internet à tendance à perdre des paquets.

What is this Mosh thing?

You don't have to use Mosh or even know about it to follow along.

We're just telling you about it because some of us think it's cool!

Mosh is "the mobile shell"

It is essentially SSH over UDP, with roaming features

It retransmits packets quickly, so it works great even on lossy connections

(Like hotel or conference WiFi)

It has intelligent local echo, so it works great even in high-latency connections

(Like hotel or conference WiFi)

It supports transparent roaming when your client IP address changes

(Like when you hop from hotel to conference WiFi)

Using Mosh

To install it:

(apt|yum|brew) install moshIt has been pre-installed on the VMs that we are using

To connect to a remote machine:

mosh user@host(It is going to establish an SSH connection, then hand off to UDP)

It requires UDP ports to be open

(By default, it uses a UDP port between 60000 and 61000)

Se connecter à notre environnement de test

- Connectez-vous sur la première VM (

node1) avec votre client SSH

- Vérifiez que vous pouvez passer sur

node2sans mot de passe:ssh node2 - Tapez

exitou^Dpour revenir ànode1

Si quoique ce soit va mal - appelez à l'aide!

Doing or re-doing the workshop on your own?

Use something like Play-With-Docker or Play-With-Kubernetes

Zero setup effort; but environment are short-lived and might have limited resources

Create your own cluster (local or cloud VMs)

Small setup effort; small cost; flexible environments

Create a bunch of clusters for you and your friends (instructions)

Bigger setup effort; ideal for group training

On travaillera (surtout) avec node1

Ces remarques s'appliquent uniquement en cas de serveurs multiples, bien sûr.

Sauf contre-indication expresse, toutes les commandes sont lancées depuis la première VM,

node1Tout code sera récupéré sur

node1uniquement.En administration classique, nous n'avons pas besoin d'accéder aux autres serveurs.

Si nous devions diagnostiquer une panne, on utiliserait tout ou partie de:

SSH (pour accéder aux logs de système, statut du daemon, etc.)

l'API Docker (pour vérifier les conteneurs lancés, et l'état du moteur de conteneurs)

Terminaux

Once in a while, the instructions will say:

"Open a new terminal."

There are multiple ways to do this:

create a new window or tab on your machine, and SSH into the VM;

use screen or tmux on the VM and open a new window from there.

You are welcome to use the method that you feel the most comfortable with.

Tmux cheatsheet

Tmux is a terminal multiplexer like screen.

You don't have to use it or even know about it to follow along.

But some of us like to use it to switch between terminals.

It has been preinstalled on your workshop nodes.

- Ctrl-b c → creates a new window

- Ctrl-b n → go to next window

- Ctrl-b p → go to previous window

- Ctrl-b " → split window top/bottom

- Ctrl-b % → split window left/right

- Ctrl-b Alt-1 → rearrange windows in columns

- Ctrl-b Alt-2 → rearrange windows in rows

- Ctrl-b arrows → navigate to other windows

- Ctrl-b d → detach session

- tmux attach → reattach to session

Versions installées

- Kubernetes 1.14.3

- Docker Engine 18.09.6

- Docker Compose 1.21.1

- Vérifier toutes les versions installées:kubectl versiondocker versiondocker-compose -v

Compatibilité entre Kubernetes et Docker

Kubernetes 1.13.x est uniquement validé avec les versions Docker Engine jusqu'à to 18.06

Kubernetes 1.14 est validé avec les versions Docker Engine versions jusqu'à 18.09

(la dernière version stable quand Kubernetes 1.14 est sorti)Est-ce qu'on vit dangereusement en installant un Docker Engine "trop récent"?

Compatibilité entre Kubernetes et Docker

Kubernetes 1.13.x est uniquement validé avec les versions Docker Engine jusqu'à to 18.06

Kubernetes 1.14 est validé avec les versions Docker Engine versions jusqu'à 18.09

(la dernière version stable quand Kubernetes 1.14 est sorti)Est-ce qu'on vit dangereusement en installant un Docker Engine "trop récent"?

Que nenni!

"Validé" = passe les tests d'intégration continue très intenses (et coûteux)

L'API Docker est versionnée, et offre une comptabilité arrière très forte.

(Si un client "parle" l'API v1.25, le Docker Engine va continuer à se comporter de la même façon)

Notre application de démo

(automatically generated title slide)

Notre application de démo

Nous allons cloner le dépôt Github sur notre

node1Le dépôt contient aussi les scripts et outils à utiliser à travers la formation.

- Cloner le dépôt sur

node1:git clone https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.training

(Vous pouvez aussi forker le dépôt sur Github et cloner votre version si vous préférez.)

Télécharger et lancer l'application

Démarrons-la avant de s'y plonger, puisque le téléchargement peut prendre un peu de temps...

Aller dans le dossier

dockercoinsdu dépôt cloné:cd ~/container.training/dockercoinsUtiliser Compose pour générer et lancer tous les conteneurs:

docker-compose up

Compose indique à Docker de construire toutes les images de conteneurs (en téléchargeant les images de base correspondantes), puis de démarrer tous les conteneurs et d'afficher les logs agrégés.

Qu'est-ce que cette application?

Qu'est-ce que cette application?

- C'est un miner de DockerCoin! 💰🐳📦🚢

Qu'est-ce que cette application?

C'est un miner de DockerCoin! 💰🐳📦🚢

Non, on ne paiera pas le café avec des DockerCoins

Qu'est-ce que cette application?

C'est un miner de DockerCoin! 💰🐳📦🚢

Non, on ne paiera pas le café avec des DockerCoins

Comment DockerCoins fonctionne

générer quelques octets aléatoires

calculer une somme de hachage

incrémenter un compteur (pour suivre la vitesse)

répéter en boucle!

Qu'est-ce que cette application?

C'est un miner de DockerCoin! 💰🐳📦🚢

Non, on ne paiera pas le café avec des DockerCoins

Comment DockerCoins fonctionne

générer quelques octets aléatoires

calculer une somme de hachage

incrémenter un compteur (pour suivre la vitesse)

répéter en boucle!

DockerCoins n'est pas une crypto-monnaie

(les seuls points communs étant "aléatoire", "hachage", et "coins" dans le nom)

DockerCoins à l'âge des microservices

DockerCoins est composée de 5 services:

rng= un service web générant des octets au hasardhasher= un service web calculant un hachage basé sur les données POST-éesworker= un processus en arrière-plan utilisantrngethasherwebui= une interface web pour le suivi du travailredis= base de données (garde un décompte, mis à jour parworker)

Ces 5 services sont visibles dans le fichier Compose de l'application, docker-compose.yml

Comment fonctionne DockerCoins

workerinvoque le service webrngpour générer quelques octets aléatoiresworkerinvoque le service webhasherpour générer un hachage de ces octetsworkerreboucle de manière infinie sur ces 2 tâcheschaque seconde,

workerécrit dansredispour indiquer combien de boucles ont été réaliséeswebuiinterrogeredis, pour calculer et exposer la "vitesse de hachage" dans notre navigateur

(Voir le diagramme en diapo suivante!)

Service discovery au pays des conteneurs

- Comment chaque service trouve l'adresse des autres?

Service discovery au pays des conteneurs

Comment chaque service trouve l'adresse des autres?

On ne code pas en dur des adresses IP dans le code.

On ne code pas en dur des FQDN dans le code, non plus.

On se connecte simplement avec un nom de service, et la magie du conteneur fait le reste

(Par magie du conteneur, nous entendons "l'astucieux DNS embarqué dynamique")

Exemple dans worker/worker.py

redis = Redis("redis")def get_random_bytes(): r = requests.get("http://rng/32") return r.contentdef hash_bytes(data): r = requests.post("http://hasher/", data=data, headers={"Content-Type": "application/octet-stream"})(Code source complet disponible ici)

Liens, nommage et découverte de service

Les conteneurs peuvent avoir des alias de réseau (résolus par DNS)

Compose dans sa version 2+ rend chaque conteneur disponible via son nom de service

Compose en version 1 rendait obligatoire la section "links"

Les alias de réseau sont automatiquement préfixé par un espace de nommage

vous pouvez avoir plusieurs applications déclarées via un service appelé

databaseles conteneurs dans l'appli bleue vont atteindre

databasevia l'IP de la base de données bleueles conteneurs dans l'appli verte vont atteindre

databasevia l'IP de la base de données verte

Montrez-moi le code!

Vous pouvez ouvrir le dépôt Github avec tous les contenus de cet atelier:

https://github.com/jpetazzo/container.trainingCette application est dans le sous-dossier dockercoins

Le fichier Compose (docker-compose.yml) liste les 5 services

redisutilise une image officielle issue du Docker Hubhasher,rng,worker,webuisont générés depuis un DockerfileChaque Dockerfile de service et son code source est stocké dans son propre dossier

(

hasherest dans le dossier hasher,rngest dans le dossier rng, etc.)

Version du format de fichier Compose

Uniquement pertinent si vous avez utilisé Compose avant 2016...

Compose 1.6 a introduit le support d'un nouveau format de fichier Compose (alias "v2")

Les services ne sont plus au plus haut niveau, mais dans une section

services.Il doit y avoir une clé

versiontout en haut du fichier, avec la valeur"2"(la chaîne de caractères, pas le chiffre)Les conteneurs sont placés dans un réseau dédié, rendant les links inutiles

Il existe d'autres différences mineures, mais la mise à jour est facile et assez directe.

Notre application à l'oeuvre

A votre gauche, la bande "arc-en-ciel" montrant les noms de conteneurs

A votre droite, nous voyons la sortie standard de nos conteneurs

On peut voir le service

workerexécutant des requêtes versrngethasherPour

rngethasher, on peut lire leur logs d'accès HTTP

Se connecter à l'interface web

"Les logs, c'est excitant et drôle" (Citation de personne, jamais, vraiment)

Le conteneur

webuiexpose un écran de contrôle web; allons-y voir.

Avec un navigateur, se connecter à

node1sur le port 8000Rappel: les alias

nodeXne sont valides que sur les noeuds eux-mêmes.Dans votre navigateur, vous aurez besoin de taper l'adresse IP de votre noeud.

Un diagramme devrait s'afficher, et après quelques secondes, une courbe en bleu va apparaître.

Pourquoi le rythme semble irrégulier?

On dirait peu ou prou que la vitesse est de 4 hachages/seconde.

Ou plus précisément: 4 hachages/secondes avec des trous reguliers à zéro

Pourquoi?

Pourquoi le rythme semble irrégulier?

On dirait peu ou prou que la vitesse est de 4 hachages/seconde.

Ou plus précisément: 4 hachages/secondes avec des trous reguliers à zéro

Pourquoi?

L'appli a en réalité une vitesse constante et régulière de 3.33 hachages/seconde.

(ce qui correspond à 1 hachage toutes les 0.3 secondes, pour certaines raisons)Oui, et donc?

La raison qui fait que ce graphe n'est pas super

Le worker ne met pas à jour le compteur après chaque boucle, mais au maximum une fois par seconde.

La vitesse est calculée par le navigateur, qui vérifie le compte à peu près une fois par seconde.

Entre 2 mise à jours consécutives, le compteur augmentera soit de 4, ou de 0 (zéro).

La vitesse perçue sera donc 4 - 4 - 0 - 4 - 4 - 0, etc.

Que peut-on conclure de tout cela?

La raison qui fait que ce graphe n'est pas super

Le worker ne met pas à jour le compteur après chaque boucle, mais au maximum une fois par seconde.

La vitesse est calculée par le navigateur, qui vérifie le compte à peu près une fois par seconde.

Entre 2 mise à jours consécutives, le compteur augmentera soit de 4, ou de 0 (zéro).

La vitesse perçue sera donc 4 - 4 - 0 - 4 - 4 - 0, etc.

Que peut-on conclure de tout cela?

- "Je suis carrément incapable d'écrire du bon code frontend" 😀 — Jérôme

Arrêter notre application

Si nous stoppons Compose (avec

^C), il demandera poliment au Docker Engine d'arrêter l'appliLe Docker Engine va envoyer un signal

TERMaux conteneursSi les conteneurs ne quittent pas assez vite, l'Engine envoie le signal

KILL

- Arrêter l'application en tapant

^C

Arrêter notre application

Si nous stoppons Compose (avec

^C), il demandera poliment au Docker Engine d'arrêter l'appliLe Docker Engine va envoyer un signal

TERMaux conteneursSi les conteneurs ne quittent pas assez vite, l'Engine envoie le signal

KILL

- Arrêter l'application en tapant

^C

Certains conteneurs quittent immédiatement, d'autres prennent plus de temps.

Les conteneurs qui ne gèrent pas le SIGTERM finissent pas être tués après 10 secs. Si nous sommes vraiment impatients, on peut taper ^C une seconde fois!

Nettoyage

- Avant de continuer, supprimons tous ces conteneurs.

- Dire à Compose de tout enlever:docker-compose down

Concepts Kubernetes

(automatically generated title slide)

Concepts Kubernetes

Kubernetes est un système de gestion de conteneurs

Il lance et gère des applications conteneurisées sur un cluster

Concepts Kubernetes

Kubernetes est un système de gestion de conteneurs

Il lance et gère des applications conteneurisées sur un cluster

Qu'est-ce que ça signifie vraiment?

Tâches de base qu'on peut demander à Kubernetes

Tâches de base qu'on peut demander à Kubernetes

- Démarrer 5 conteneurs basés sur l'image

atseashop/api:v1.3

Tâches de base qu'on peut demander à Kubernetes

Démarrer 5 conteneurs basés sur l'image

atseashop/api:v1.3Placer un load balancer interne devant ces conteneurs

Tâches de base qu'on peut demander à Kubernetes

Démarrer 5 conteneurs basés sur l'image

atseashop/api:v1.3Placer un load balancer interne devant ces conteneurs

Démarrer 10 conteneurs basés sur l'image

atseashop/webfront:v1.3

Tâches de base qu'on peut demander à Kubernetes

Démarrer 5 conteneurs basés sur l'image

atseashop/api:v1.3Placer un load balancer interne devant ces conteneurs

Démarrer 10 conteneurs basés sur l'image

atseashop/webfront:v1.3Placer un load balancer public devant ces conteneurs

Tâches de base qu'on peut demander à Kubernetes

Démarrer 5 conteneurs basés sur l'image

atseashop/api:v1.3Placer un load balancer interne devant ces conteneurs

Démarrer 10 conteneurs basés sur l'image

atseashop/webfront:v1.3Placer un load balancer public devant ces conteneurs

C'est Black Friday (ou Noël!), le trafic explose, agrandir notre cluster et ajouter des conteneurs

Tâches de base qu'on peut demander à Kubernetes

Démarrer 5 conteneurs basés sur l'image

atseashop/api:v1.3Placer un load balancer interne devant ces conteneurs

Démarrer 10 conteneurs basés sur l'image

atseashop/webfront:v1.3Placer un load balancer public devant ces conteneurs

C'est Black Friday (ou Noël!), le trafic explose, agrandir notre cluster et ajouter des conteneurs

Nouvelle version! Remplacer les conteneurs avec la nouvelle image

atseashop/webfront:v1.4

Tâches de base qu'on peut demander à Kubernetes

Démarrer 5 conteneurs basés sur l'image

atseashop/api:v1.3Placer un load balancer interne devant ces conteneurs

Démarrer 10 conteneurs basés sur l'image

atseashop/webfront:v1.3Placer un load balancer public devant ces conteneurs

C'est Black Friday (ou Noël!), le trafic explose, agrandir notre cluster et ajouter des conteneurs

Nouvelle version! Remplacer les conteneurs avec la nouvelle image

atseashop/webfront:v1.4Continuer de traiter les requêtes pendant la mise à jour; renouveler mes conteneurs un à la fois

D'autres choses que Kubernetes peut faire pour nous

Montée en charge basique

Déploiement Blue/Green, déploiement canary

Services de longue durée, mais aussi des tâches par lots (batch)

Surcharger notre cluster et évincer les tâches de basse priorité

Lancer des services à données persistentes (bases de données, etc.)

Contrôle d'accès assez fin, pour définir quelle action est autorisée pour qui sur quelle ressources.

Intégrer les services tiers (catalogue de services)

Automatiser des tâches complexes (opérateurs)

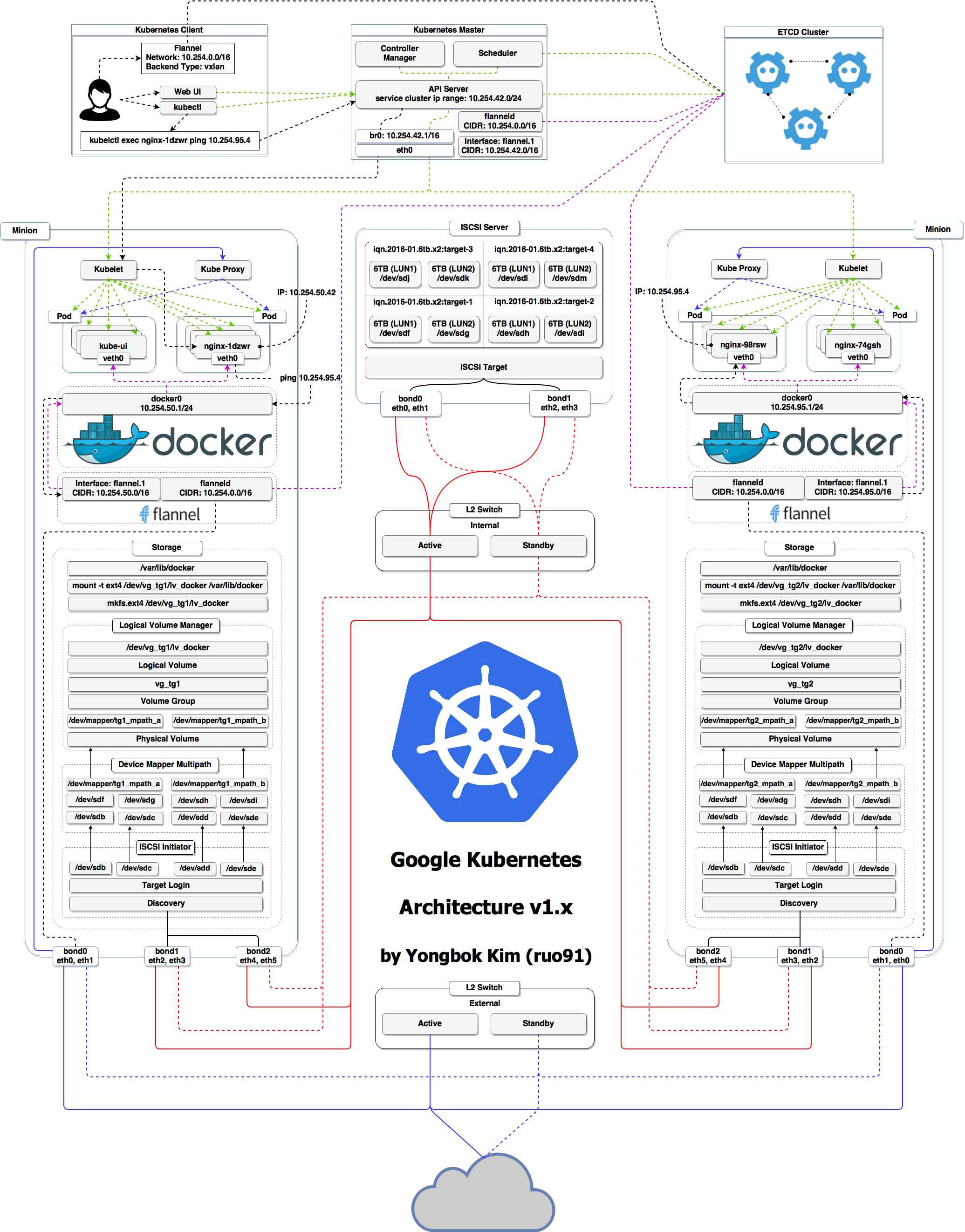

Architecture Kubernetes

Ha ha ha ha

OK, je voulais juste vous faire peur, c'est plus simple que ça ❤️

Crédits

Le premier schéma est un cluster Kubernetes avec du stockage sur l'iSCSI multi-path

(Grâce à Yongbok Kim)

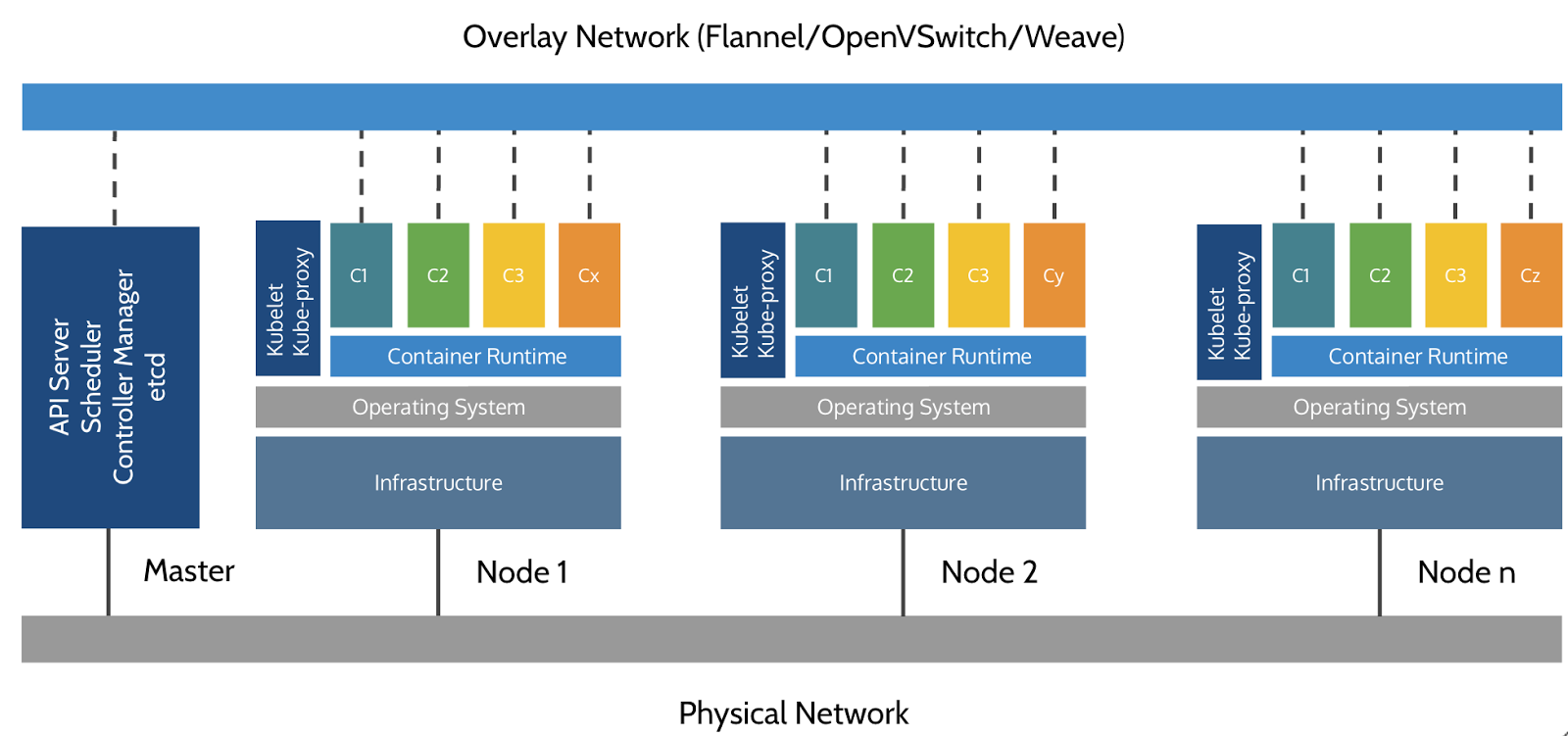

Le second est une représentation simplifiée d'un cluster Kubernetes

(Grâce à Imesh Gunaratne)

Architecture de Kubernetes: les nodes

Les nodes qui font tourner nos conteneurs ont aussi une collection de services:

un moteur de conteneurs (typiquement Docker)

kubelet (l'agent de node)

kube-proxy (un composant réseau nécessaire mais pas suffisant)

Les nodes étaient précédemment appelées des "minions"

(On peut encore rencontrer ce terme dans d'anciens articles ou documentation)

Architecture Kubernetes: le plan de contrôle

La logique de Kubernetes (ses "méninges") est une collection de services:

Le serveur API (notre point d'entrée pour toute chose!)

des services principaux comme l'ordonnanceur et le contrôleur

etcd(une base clé-valeur hautement disponible; la "base de données" de Kubernetes)

Ensemble, ces services forment le plan de contrôle de notre cluster

Le plan de contrôle est aussi appelé le "master"

Plan de contrôle sur des nodes spéciales

Il est commun de réserver une node dédiée au plan de contrôle

(Excepté pour les cluster de développement à node unique, comme avec minikube)

Cette node est alors appelée un "master"

(Oui, c'est ambigu: est-ce que le "master" est une node, ou tout le plan de contrôle?)

Les applis normales sont interdites de tourner sur cette node

(En utilisant un mécanisme appelé "taints")

Pour de la haute dispo, chaque service du plan de contrôle doit être résilient

Le plan de contrôle est alors répliqué sur de multiples noeuds

(On parle alors d'installation "multi-master")

Lancer le plan de contrôle sans conteneurs

Les services du plan de contrôle peuvent tourner avec ou sans conteneurs

Par exemple: puisque

etcdest un service critique, certains le déploient directement sur un cluster dédié (sans conteneurs)(C'est illustré dans le premier schéma "super compliqué")

Dans certaines offres commerciales Kubernetes (par ex. AKS, GKE, EKS), le plan de contrôle est invisible

(On "voit" juste un point d'entrée Kubernetes API)

Dans ce cas, il n'y a pas de node "master"

Pour cette raison, il est plus précis de parler de "plan de contrôle" plutôt que de "master".

Docker est-il obligatoire à tout prix?

Non!

Docker est-il obligatoire à tout prix?

Non!

Par défaut, Kubernetes choisit le Docker Engine pour lancer les conteneurs

On pourrait utiliser

rkt("Rocket") par CoreOSOu exploiter d'autre moteurs via la Container Runtime Interface

(comme CRI-O, ou containerd)

Devrait-on utiliser Docker?

Oui!

Devrait-on utiliser Docker?

Oui!

Dans cet atelier, on lancera d'abord notre appli sur un seul noeud

On devra générer les images et les envoyer à la ronde

On pourrait se débrouiller sans Docker

(et être diagnostiqué du syndrome NIH¹)Docker est à ce jour le moteur de conteneurs le plus stable

(mais les alternatives mûrissent rapidement)

Devrait-on utiliser Docker?

Sur nos environnements de développement, les pipelines CI ... :

Oui, très certainement

Sur nos serveurs de production:

Oui (pour aujourd'hui)

Probablement pas (dans le futur)

Pour plus d'infos sur CRI sur le blog Kubernetes

Interagir avec Kubernetes

Le dialogue avec Kubernetes s'effectue via une API RESTful, la plupart du temps.

L'API Kubernetes définit un tas d'objets appelés resources

Ces ressources sont organisées par type, ou

Kind(dans l'API)Elle permet de déclarer, lire, modifier et supprimer les resources

Quelques types de ressources communs:

- node (une machine - physique ou virtuelle - de notre cluster)

- pod (groupe de conteneurs lancés ensemble sur une node)

- service (point d'entrée stable du réseau pour se connecter à un ou plusieurs conteneurs)

Et bien plus!

On peut afficher la liste complète avec

kubectl api-resources

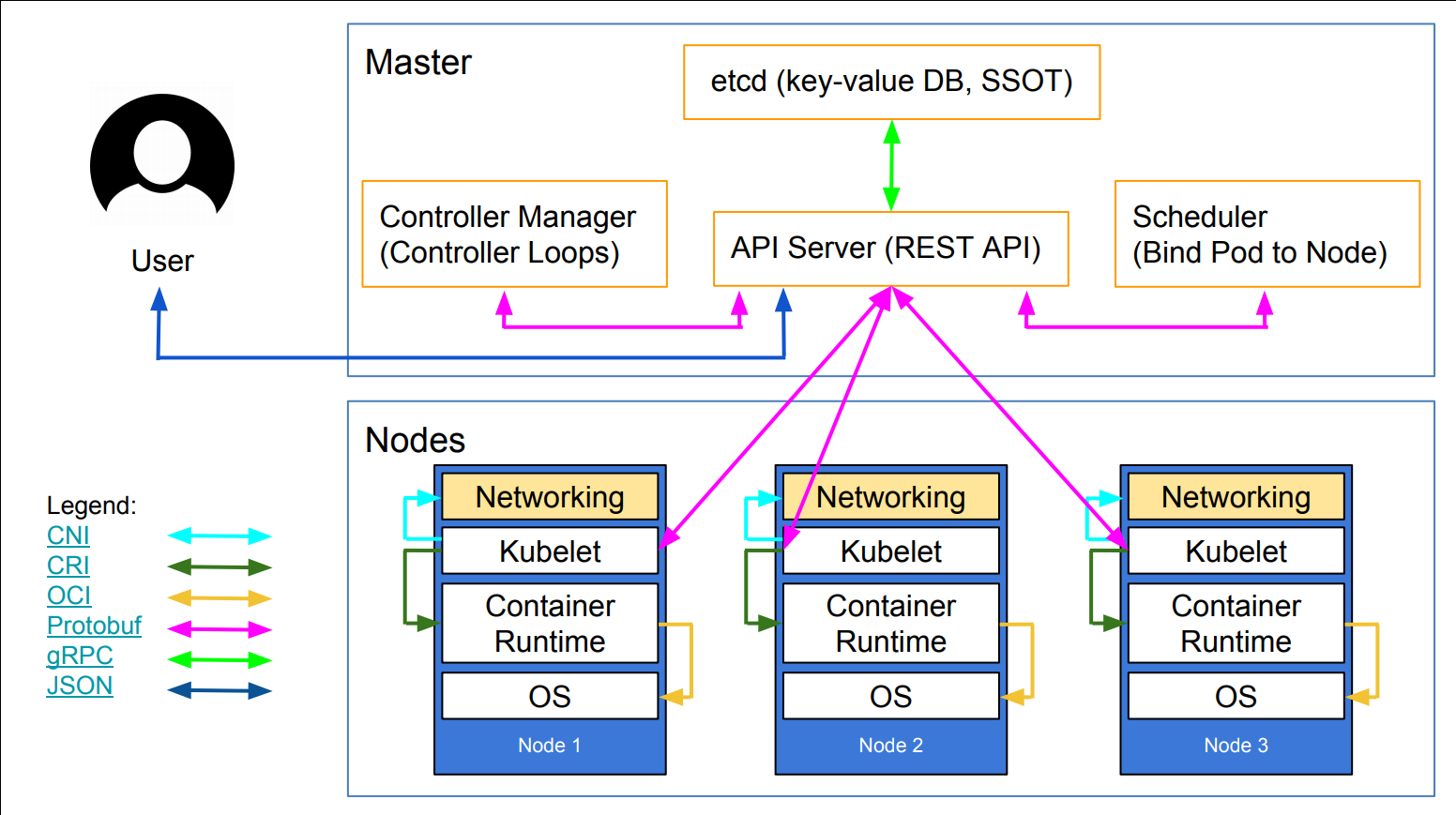

Crédits

Le premier diagramme est une grâcieuseté de Lucas Käldström, dans cette présentation

- c'est l'un des meilleurs diagrammes d'architecture Kubernetes disponibles!

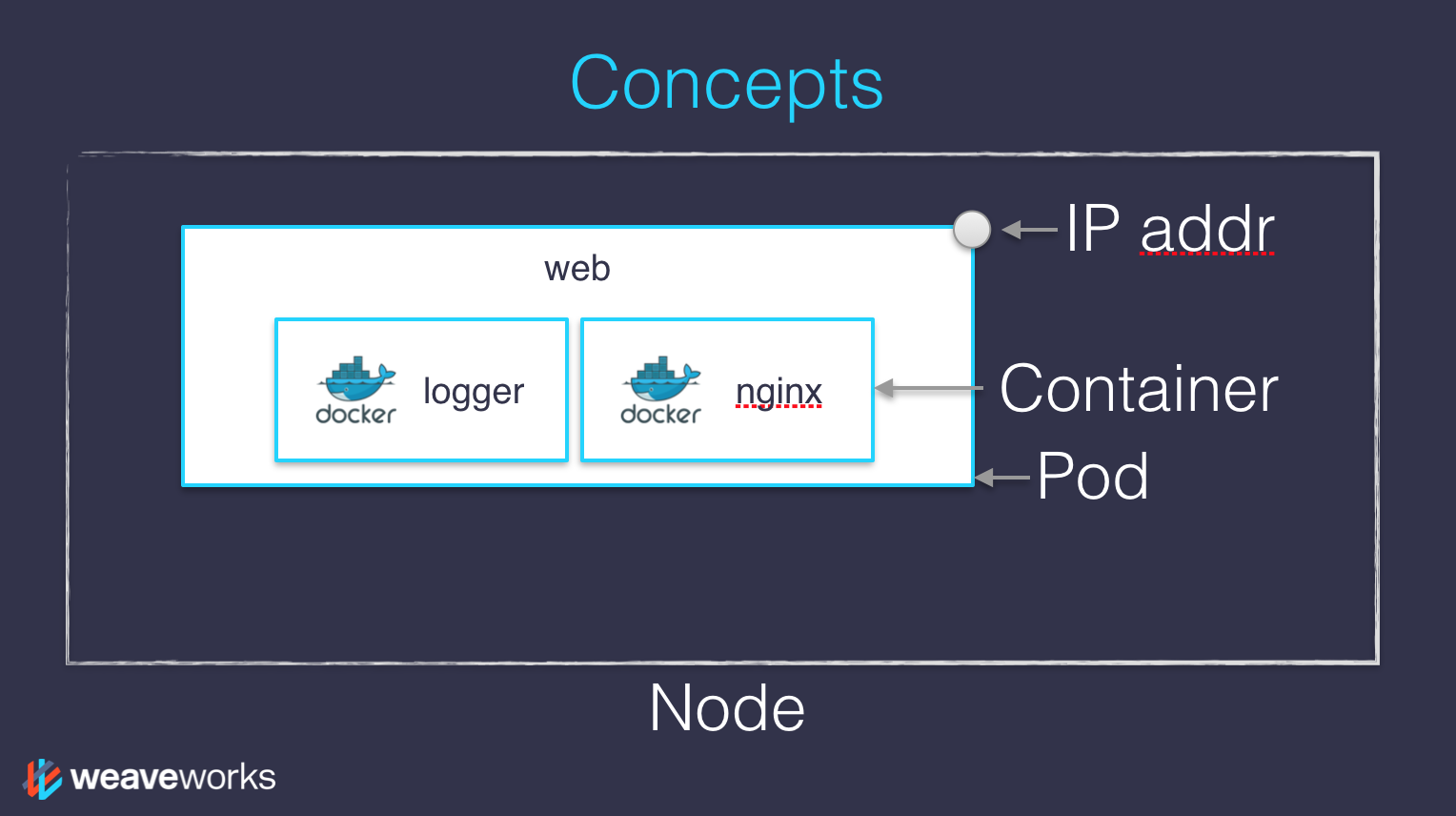

Le second diagramme est une grâcieuseté de Weave Works

un pod peut avoir plusieurs conteneurs qui travaillent ensemble

les adresses IP sont associées aux pods, pas aux conteneurs eux-mêmes

Les deux diagrammes sont utilisés avec la permission de leurs auteurs.

Déclaratif vs Impératif

(automatically generated title slide)

Déclaratif vs Impératif

Notre orchestrateur de conteneurs insiste fortement sur sa nature déclarative

Déclaratif:

Je voudrais une tasse de thé

Impératif:

Faire bouillir de l'eau. Verser dans la théière. Ajouter les feuilles de thé. Infuser un moment. Servir dans une tasse.

Déclaratif vs Impératif

Notre orchestrateur de conteneurs insiste fortement sur sa nature déclarative

Déclaratif:

Je voudrais une tasse de thé

Impératif:

Faire bouillir de l'eau. Verser dans la théière. Ajouter les feuilles de thé. Infuser un moment. Servir dans une tasse.

Le mode déclaratif semble plus simple au début...

Déclaratif vs Impératif

Notre orchestrateur de conteneurs insiste fortement sur sa nature déclarative

Déclaratif:

Je voudrais une tasse de thé

Impératif:

Faire bouillir de l'eau. Verser dans la théière. Ajouter les feuilles de thé. Infuser un moment. Servir dans une tasse.

Le mode déclaratif semble plus simple au début...

... tant qu'on sait comment préparer du thé

Déclaratif vs Impératif

Ce que le mode déclaratif devrait vraiment être:

Je voudrais une tasse de thé, obtenue en versant une infusion¹ de feuilles de thé dans une tasse.

Déclaratif vs Impératif

Ce que le mode déclaratif devrait vraiment être:

Je voudrais une tasse de thé, obtenue en versant une infusion¹ de feuilles de thé dans une tasse.

¹Une infusion est obtenue en laissant l'objet infuser quelques minutes dans l'eau chaude².

Déclaratif vs Impératif

Ce que le mode déclaratif devrait vraiment être:

Je voudrais une tasse de thé, obtenue en versant une infusion¹ de feuilles de thé dans une tasse.

¹Une infusion est obtenue en laissant l'objet infuser quelques minutes dans l'eau chaude².

²Liquide chaud obtenu en le versant dans un contenant³ approprié et le placer sur la gazinière.

Déclaratif vs Impératif

Ce que le mode déclaratif devrait vraiment être:

Je voudrais une tasse de thé, obtenue en versant une infusion¹ de feuilles de thé dans une tasse.

¹Une infusion est obtenue en laissant l'objet infuser quelques minutes dans l'eau chaude².

²Liquide chaud obtenu en le versant dans un contenant³ approprié et le placer sur la gazinière.

³Ah, finalement, des conteneurs! Quelque chose qu'on maitrise. Mettons-nous au boulot, n'est-ce pas?

Déclaratif vs Impératif

Ce que le mode déclaratif devrait vraiment être:

Je voudrais une tasse de thé, obtenue en versant une infusion¹ de feuilles de thé dans une tasse.

¹Une infusion est obtenue en laissant l'objet infuser quelques minutes dans l'eau chaude².

²Liquide chaud obtenu en le versant dans un contenant³ approprié et le placer sur la gazinière.

³Ah, finalement, des conteneurs! Quelque chose qu'on maitrise. Mettons-nous au boulot, n'est-ce pas?

Saviez-vous qu'il existait une norme ISO spécifiant comment infuser le thé?

Déclaratif vs Impératif

Système impératifs:

plus simple

si une tache est interrompue, on doit la redémarrer de zéro

Système déclaratifs:

si une tache est interrompue (ou si on arrive en plein milieu de la fête), on peut déduire ce qu'il manque, et on complète juste par ce qui est nécessaire.

on doit être en mesure d'observer le système

... et de calculer un "diff" entre ce qui tourne en ce moment et ce que nous souhaitons

Déclaratif vs Impératif dans Kubernetes

Pratiquement tout ce que nous lançons sur Kubernetes est déclaré dans une spec

Tout ce qu'on peut faire est écrire un spec et la pousser au serveur API

(en déclarant des ressources comme Pod ou Deployment)

Le serveur API va valider cette spec (la rejeter si elle est invalide)

Puis la stocker dans etcd

Un controller va "repérer" cette spécification et réagir en conséquence

Réconciliation d'état

Gardez un oeil sur les champs

specdans les fichiers YAML plus tard!La spec décrit comment on voudrait que ce truc tourne

Kubernetes va réconcilier l'état courant avec la spec

(techniquement, c'est possible via un tas de controllers)Quand on veut changer une ressources, on modifie la spec

Kubernetes va alors faire converger cette ressource

Modèle réseau de Kubernetes

(automatically generated title slide)

Modèle réseau de Kubernetes

En un mot comme en cent:

Notre cluster (nodes et pods) est un grand réseau IP tout plat.

Modèle réseau de Kubernetes

En un mot comme en cent:

Notre cluster (nodes et pods) est un grand réseau IP tout plat.

Dans le détail:

toutes les nodes doivent être accessibles les unes aux autres, sans NAT

tous les pods doivent être accessibles les uns aux autres, sans NAT

pods et nodes doivent être accessibles les uns aux autres, sans NAT

chaque pod connait sa propore adresse IP (sans NAT)

les adresses IP sont assignées par l'implémentation du réseau (le plugin)

Kubernetes ne force pas une implémentation particulière

Modèle réseau de Kubernetes: le bon

Tout peut se connecter à tout

Pas de traduction d'adresse

Pas de traduction de port

Pas de nouveau protocole

L'implémentation réseau peut décider comment allouer les adresses

Les adresses IP n'ont pas à être "portables" d'une node à une autre.

(On peut avoir par ex. un sous-réseau par node et utiliser une topologie simple)

La spécification est assez simple pour permettre différentes implémentations variées

Modèle réseau de Kubernetes: le moins bon

Tout peut se connecter à tout

si on cherche de la sécurité, on devra rajouter des règles réseau

l'implémentation réseau que vous choisirez devra offrir cette fonction

Il y a littéralement des dizaines d'implémentations dans le monde

(Pas moins de 15 sont mentionnées dans la documentation Kubernetes)

Les pods ont une connectivité de niveau 3 (IP), et les services de niveau 4 (TCP ou UDP)

(Les services sont associés à un seul port TCP ou UDP; pas de groupe de ports ou de paquets IP arbitraires)

kube-proxyest sur le chemin de données quand il se connecte à un pod ou conteneur,

et ce n'est pas particulièrement rapide (il s'appuie sur du proxy utilisateur ou iptables)

Modèle réseau de Kubernetes: en pratique

Les nodes que nous avons à notre disposition utilisent Weave

On ne recommande pas Weave plus que ça, c'est juste que "Ca Marche Pour Nous"

Pas d'inquiétude à propos des réserves sur la performance

kube-proxySauf si vous:

- saturez régulièrement des interfaces réseaux 10Gbps

- comptez les flux de paquets par millions à la seconde

- lancez des plate-formes VOIP ou de jeu de haut trafic

- faites des trucs bizarres qui lancent des millions de connexions simultanées

(auquel cas vous êtes déjà familier avec l'optimisation du noyau)

Si nécessaire, des alternatives à

kube-proxyexistent, comme:kube-router

La CNI (Container Network Interface)

La CNI est une spécification complète à destination des plugins réseau.

Quand un nouveau pod est créé, Kubernetes délègue la config réseau aux plugins CNI.

(ça peut être un seul plugin, ou une combinaison de plugins, chacun spécialisé dans une tache)

Généralement, un plugin CNI va:

allouer une adresse IP (en appelant un plugin IPAM)

ajouter une interface réseau dans le namespace réseau du pod

configurer l'interface ainsi que les routes minimum, etc.

Tous les plugins CNI ne naissent pas égaux

(par ex. il ne supportent pas tous les politiques de réseau, obligatoires pour isoler les pods)

Plusieurs cibles mouvantes

Le "réseau pod-à-pod" ou "réseau pod":

fournit la communication entre pods et nodes

est généralement implémenté via des plugins CNI

Le "réseau pod-à-service":

fournit la communication interne et la répartition de charge

est généralement implémenté avec kube-proxy (ou par ex. kube-router)

Network policies :

jouent le rôle de firewall et de couche d'isolation

peuvent être livrées avec le "réseau pod" ou fournit par un autre composant

Encore plus de cibles mouvantes

Le trafic entrant peut être géré par plusieurs composants:

quelque chose comme kube-proxy ou kube-router (pour les services NodePort)

les load balancers (idéalement, connectés au réseau pod)

En théorie, il est possible d'utiliser plusieurs réseaux pods en parallèle

(avec des "meta-plugins" comme CNI-Genie ou Multus)

Quelques solutions peuvent remplir plusieurs de ces rôles

(par ex. kube-router peut être installé pour implémenter le réseau pod et/ou les network policies et/ou remplacer kube-proxy)

Premier contact avec kubectl

(automatically generated title slide)

Premier contact avec kubectl

kubectlest (presque) le seul outil dont nous aurons besoin pour parler à KubernetesC'est un outil en ligne de commande très riche, autour de l'API Kubernetes

(Tout ce qu'on peut faire avec

kubectl, est directement exécutable via l'API)Sur nos machines, on trouvera un fichier

~/.kube/configavec:l'adresse de l'API Kubernetes

le chemin vers nos certificats TLS d'identification

On peut aussi utiliser l'option

--kubeconfigpour forcer un fichier de configOu passer directement

--server,--user, etc.kubectlse prononce "Cube Cé Té Elle", "Cube coeuteule", "Cube coeudeule"

kubectl get

- Jetons un oeil aux ressources

Nodeaveckubectl get!

Examiner la composition de notre cluster:

kubectl get nodeCes commandes sont équivalentes:

kubectl get nokubectl get nodekubectl get nodes

Obtenir un affichage version "machine"

kubectl getpeut afficher du JSON, YAML ou un format personnalisé

Sortir plus d'info sur les nodes

kubectl get nodes -o wideRécupérons du YAML:

kubectl get no -o yamlCe bout de

kind: Listtout à la fin? C'est le type de notre résultat!

User et abuser de kubectl et jq

- C'est super facile d'afficher ses propres rapports

- Montrer la capacité de tous nos noeuds sous forme de flux d'objets JSON:kubectl get nodes -o json |jq ".items[] | {name:.metadata.name} + .status.capacity"

Qu'est-ce qui tourne là-dessous?

kubectldispose de capacité d'introspection solidesOn peut lister les types de ressources en lançant

kubectl api-resources

(Sur Kubernetes 1.10 et les versions précédentes, il fallait taperkubectl get)Pour détailler une ressource, c'est:

kubectl explain typeLa définition d'un type de ressource s'affiche avec:

kubectl explain node.spec- ou afficher la définition complète de tous les champs et sous-champs:kubectl explain node --recursive

Introspection vs. documentation

On peut accéder à la même information en lisant la documentation d'API

La doc est habituellement plus facile à lire, mais:

- elle ne montrera par les types (comme les Custom Resource Definitions)

- attention à bien utiliser la version correcte

kubectl api-resourcesandkubectl explainfont de l'introspection(en s'appuyant sur le serveur API, pour récupérer des définitions de types exactes)

Nommage de types

Les ressources les plus communes ont jusqu'à 3 formes de noms:

singulier (par ex.

node,service,deployment)pluriel (par ex.

nodes,services,deployments)court (par ex.

no,svc,deploy)

Certaines ressources n'ont pas de nom court

Endpointsn'ont qu'une forme au pluriel(parce que même une seule ressource

Endpointsest en fait une liste d'endpoints)

Détailler l'affichage

On peut taper

kubectl get -o yamlpour un détail complet d'une ressourceToutefois, le format YAML peut être à la fois trop verbeux et incomplet

Par exemple,

kubectl get node node1 -o yamlest:trop verbeux (par ex. la liste des images disponibles sur cette node)

incomplet (car on ne voit pas les pods qui y tournent)

difficile à lire pour un administrateur humain

Pour une vue complète, on peut utiliser

kubectl describeen alternative.

kubectl describe

kubectl describerequiert un type de ressource et (en option) un nom de ressourceIl est possible de fournir un préfixe de nom de ressource

(tous les objets contenant ce nom seront affichés)

kubectl describeva récupérer quelques infos de plus sur une ressource

Jeter un oeil aux infos de

node1avec une de ces commandes:kubectl describe node/node1kubectl describe node node1

(On devrait voir un tas de pods du plan de contrôle)

Services

Un service est un point d'entrée stable pour se connecter à "quelque chose"

(Dans la proposition initiale, on appelait ça un "portail")

- Lister les services sur notre cluster avec une de ces commandes:kubectl get serviceskubectl get svc

Services

Un service est un point d'entrée stable pour se connecter à "quelque chose"

(Dans la proposition initiale, on appelait ça un "portail")

- Lister les services sur notre cluster avec une de ces commandes:kubectl get serviceskubectl get svc

Il y a déjà un service sur notre cluster: l'API Kubernetes elle-même.

services ClusterIP

Un service

ClusterIPest interne, disponible uniquement depuis le clusterC'est utile pour faire l'introspection depuis l'intérieur de conteneurs.

Essayer de se connecter à l'API:

curl -k https://10.96.0.1-kest spécifié pour désactiver la vérification de certificatAttention à bien remplacer 10.96.0.1 avec l'IP CLUSTER affichée par

kubectl get svc

NB :sur Docker for Desktop, l'API n'est accessible que sur https://localhost:6443/

services ClusterIP

Un service

ClusterIPest interne, disponible uniquement depuis le clusterC'est utile pour faire l'introspection depuis l'intérieur de conteneurs.

Essayer de se connecter à l'API:

curl -k https://10.96.0.1-kest spécifié pour désactiver la vérification de certificatAttention à bien remplacer 10.96.0.1 avec l'IP CLUSTER affichée par

kubectl get svc

NB :sur Docker for Desktop, l'API n'est accessible que sur https://localhost:6443/

L'erreur que vous voyez était attendue: l'API Kubernetes exige une identification.

Lister les conteneurs qui tournent

Les conteneurs existent à travers des pods.

Un pod est un groupe de conteneurs:

qui tournent ensemble (sur le même noeud)

qui partagent des ressources (RAM, CPU; mais aussi réseau et volumes)

- Lister les pods de notre cluster:kubectl get pods

Lister les conteneurs qui tournent

Les conteneurs existent à travers des pods.

Un pod est un groupe de conteneurs:

qui tournent ensemble (sur le même noeud)

qui partagent des ressources (RAM, CPU; mais aussi réseau et volumes)

- Lister les pods de notre cluster:kubectl get pods

Ce ne sont pas là les pods que nous cherchons. Mais où sont-ils alors?!?

Namespaces

- Les espaces de nommage (namespaces) nous permettent de cloisonner des ressources.

- Lister les namespaces de notre cluster avec une de ces commandes:kubectl get namespaceskubectl get namespacekubectl get ns

Namespaces

- Les espaces de nommage (namespaces) nous permettent de cloisonner des ressources.

- Lister les namespaces de notre cluster avec une de ces commandes:kubectl get namespaceskubectl get namespacekubectl get ns

Vous savez quoi... Ce machin kube-system m'a l'air suspect.

En fait, je suis plutôt sûr de l'avoir vu tout à l'heure, quand on a tapé:

kubectl describe node node1

Accéder aux namespaces

Par défaut,

kubectlutilise le namespace...defaultOn peut montrer toutes les ressources avec

--all-namespaces

.exercise[

Lister les pods à travers tous les namespaces:

kubectl get pods --all-namespacesDepuis Kubernetes 1.14, on peut aussi taper

-Apour faire plus court:kubectl get pods -A

Et voici nos pods système!

A quoi servent ces pods du plan de contrôle?

etcdest notre serveur etcdkube-apiserverest le serveur APIkube-controller-manageretkube-schedulersont d'autres composants maîtrecorednsfournit une découverte de services basé sur le DNS (il remplace kube-dns depuis 1.11)kube-proxytourne sur chaque node et gère le mapping de ports etc.weaveest le composant qui gère les réseaux superposés sur chaque noeudla colonne

READYindique le nombre de conteneurs dans chaque podles pods avec un nom qui finit en

-node1sont les composants maître

ils sont spécifiquement "scotchés" au noeud maître.

Viser un autre namespace

- On peut aussi examiner un autre namespace (que

default)

- Lister uniquement les pods du namespace

kube-system:kubectl get pods --namespace=kube-systemkubectl get pods -n kube-system

Namespaces selon les commandes kubectl

On peut combiner

-n/--namespaceavec presque toute commandeExemple:

kubectl create --namespace=Xpour créer quelque chose dans le namespace X

On peut utiliser

-A/--all-namespacesavec la plupart des commandes qui manipulent plein d'objets à la foisExemples:

kubectl deletesupprime des ressources à travers plusieurs namespaceskubectl labelajoute/supprime des labels à travers plusieurs namespaces

Qu'en est-il de ce kube-public?

- Lister les pods dans le namespace

kube-public:kubectl -n kube-public get pods

Rien!

kube-public est créé par kubeadm et utilisé pour établie une sécurité de base

Explorer kube-public

- Le seul objet intéressant dans

kube-publicest unConfigMapnommécluster-info

Lister les ConfigMaps dans le namespace

kube-public:kubectl -n kube-public get configmapsInspecter

cluster-info:kubectl -n kube-public get configmap cluster-info -o yaml

Noter l'URI selfLink: /api/v1/namespaces/kube-public/configmaps/cluster-info

On pourrait en avoir besoin!

Accéder à cluster-info

Plus tôt, en interrogeant le serveur API, on a reçu une réponse

ForbiddenMais

cluster-infoest lisible par tous (y compris sans authentification)

- Récupérer

cluster-info:curl -k https://10.96.0.1/api/v1/namespaces/kube-public/configmaps/cluster-info

Nous sommes capables d'accéder à

cluster-info(sans auth)Il contient un fichier

kubeconfig

Récupérer kubeconfig

- On peut facilement extraire le conenu du fichier

kubeconfigde cette ConfigMap

- Afficher le contenu de

kubeconfig:curl -sk https://10.96.0.1/api/v1/namespaces/kube-public/configmaps/cluster-info \| jq -r .data.kubeconfig

Ce fichier contient l'adresse canonique du serveur d'API, et la clé publique du CA.

Ce fichier ne contient pas les clés client ou tokens

Ce ne sont pas des infos sensibles, mais c'est essentiel pour établir une connexion sécurisée.

Qu'en est-il de kube-node-lease?

Depuis Kubernetes 1.14, il y a un namespace

kube-node-lease(ou dès la version 1.13 si la fonction NodeLease était activée)

Ce namespace contient un objet Lease par node

Un Node lease est une nouvelle manière d'implémenter les heartbeat de node

(c'est-à-dire qu'une node va contacter le master de temps à autre et dire "Je suis vivant!")

Pour plus de détails, voir KEP-0009 ou la doc de contrôleur de node k8s/kubectlget.md

Installer Kubernetes

(automatically generated title slide)

Installer Kubernetes

- Comment avons-nous installé les clusters Kubernetes à qui on parle?

Installer Kubernetes

- Comment avons-nous installé les clusters Kubernetes à qui on parle?

On est passé par

kubeadmsur des VMs fraîchement installées avec Ubuntu LTSInstaller Docker

Installer les paquets Kubernetes

Lancer

kubeadm initsur la première node (c'est ce qui va déployer le plan de contrôle)Installer Weave (la couche réseau overlay)

(cette étape consiste en une seule commandekubectl apply; voir plus loin)Lancer

kubeadm joinsur les autres nodes (avec le jeton fourni parkubeadm init)Copier le fichier de configuration généré par

kubeadm init

Allez voir README d'installation des VMs pour plus de détails.

Inconvénients kubeadm

N'installe ni Docker ni autre moteur de conteneurs

N'installe pas de réseau overlay

N'installe pas de mode multi-maître (pas de haute disponibilité)

Inconvénients kubeadm

N'installe ni Docker ni autre moteur de conteneurs

N'installe pas de réseau overlay

N'installe pas de mode multi-maître (pas de haute disponibilité)

(En tout cas... pas encore!) Même si c'est une fonction expérimentale en version 1.12.)

Inconvénients kubeadm

N'installe ni Docker ni autre moteur de conteneurs

N'installe pas de réseau overlay

N'installe pas de mode multi-maître (pas de haute disponibilité)

(En tout cas... pas encore!) Même si c'est une fonction expérimentale en version 1.12.)

"C'est quand même le double de travail par rapport à un cluster Swarm 😕" -- Jérôme

Autres options de déploiement

Si vous êtes sur Azure: AKS

Si vous êtes sur Google Cloud: GKE

Agnostique au cloud (AWS/DO/GCE (beta)/vSphere(alpha)): kops

Sur votre machine locale: minikube, kubespawn, Docker Desktop

Si vous avez un déploiement spécifique: kubicorn

Sans doute à ce jour l'outil le plus proche d'une solution multi-cloud/hybride, mais encore en développement.

Encore plus d'options de déploiement

Si vous aimez Ansible: kubespray

Si vous aimez Terraform: typhoon

Si vous aimez Terraform et Puppet: tarmak

Vous pouvez aussi apprendre à installer chaque composant manuellement, avec l'excellent tutoriel Kubernetes The Hard Way

Kubernetes The Hard Way est optimisé pour l'apprentissage, ce qui implique de prendre les détours obligatoires à la compréhension de chaque étape nécessaire pour la construction d'un cluster Kubernetes.

Il y a aussi nombre d'options commerciales disponibles!

Pour une liste plus complète, veuillez consulter la documentation Kubernetes:

on y trouve un super guide pour choisir la bonne piste

Lancer nos premiers conteneurs sur Kubernetes

(automatically generated title slide)

Lancer nos premiers conteneurs sur Kubernetes

- Commençons par le commencement: on ne lance pas "un" conteneur

Lancer nos premiers conteneurs sur Kubernetes

Commençons par le commencement: on ne lance pas "un" conteneur

On va lancer un pod, et dans ce pod, on fera tourner un seul conteneur

Lancer nos premiers conteneurs sur Kubernetes

Commençons par le commencement: on ne lance pas "un" conteneur

On va lancer un pod, et dans ce pod, on fera tourner un seul conteneur

Dans ce conteneur, qui est dans le pod, nous allons lancer une simple commande

pingPuis nous allons démarrer plusieurs exemplaires du pod.

Démarrer un simple pod avec kubectl run

- On doit spécifier au moins un nom et l'image qu'on veut utiliser.

- Lancer un ping sur

1.1.1.1, le serveur DNS public de Cloudflare:kubectl run pingpong --image alpine ping 1.1.1.1

Démarrer un simple pod avec kubectl run

- On doit spécifier au moins un nom et l'image qu'on veut utiliser.

- Lancer un ping sur

1.1.1.1, le serveur DNS public de Cloudflare:kubectl run pingpong --image alpine ping 1.1.1.1

(A partir de Kubernetes 1.12, un message s'affiche nous indiquant que

kubectl run est déprécié. Laissons ça de côté pour l'instant.)

Dans les coulisses de kubectl run

- Jetons un oeil aux ressources créées par

kubectl run

- Lister tous types de ressources:kubectl get all

Dans les coulisses de kubectl run

- Jetons un oeil aux ressources créées par

kubectl run

- Lister tous types de ressources:kubectl get all

On devrait y voir quelque chose comme:

deployment.apps/pingpong(le deployment que nous venons juste de déclarer)replicaset.apps/pingpong-xxxxxxxxxx(un replica set généré par ce déploiement)pod/pingpong-xxxxxxxxxx-yyyyy(un pod généré par le replica set)

Note: à partir de 1.10.1, les types de ressources sont affichés plus en détail.

Que représentent ces différentes choses?

Un deployment est une structure de haut niveau

permet la montée en charge, les mises à jour, les retour-arrière

plusieurs déploiements peuvent être cumulés pour implémenter un canary deployment

délègue la gestion des pods aux replica sets

Un replica set est une structure de bas niveau

s'assure qu'un nombre de pods identiques est lancé

permet la montée en chage

est rarement utilisé directement

- Un replication controlller est l'ancêtre (déprécié) du replica set

Notre déploiement pingpong

kubectl rundéclare un deployment,deployment.apps/pingpong

NAME DESIRED CURRENT UP-TO-DATE AVAILABLE AGEdeployment.apps/pingpong 1 1 1 1 10m- Ce déploiement a généré un replica set,

replicaset.apps/pingpong-xxxxxxxxxx

NAME DESIRED CURRENT READY AGEreplicaset.apps/pingpong-7c8bbcd9bc 1 1 1 10m- Ce replica set a créé un pod,

pod/pingpong-xxxxxxxxxx-yyyyy

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGEpod/pingpong-7c8bbcd9bc-6c9qz 1/1 Running 0 10mNous verrons plus tard comment ces gars vivent ensemble pour:

- la montée en charge, la haute disponibilité, les mises à jour en continu

Afficher la sortie du conteneur

Essayons la commande

kubectl logsOn lui passera soit un nom de pod ou un type/name

(Par ex., si on spécifie un déploiement ou un replica set, il nous sortira le premier pod qu'il contient)

Sauf instruction expresse, la commande n'affichera que les logs du premier conteneur du pod

(Heureusement qu'il n'y en a qu'un chez nous!)

- Afficher le résultat de notre commande

ping:kubectl logs deploy/pingpong

Suivre les logs en temps réel

Tout comme

docker logs,kubectl logssupporte des options bien pratiques:-f/--followpour continuer à afficher les logs en temps réel (à latail -f)--tailpour indiquer combien de lignes on veut afficher (depuis la fin)--sincepour afficher les logs après un certain timestamp

- Voir les derniers logs de notre commande

ping:kubectl logs deploy/pingpong --tail 1 --follow

Escalader notre application

- On peut ajouter plusieurs exemplaires de notre conteneur (notre pod, pour être plus précis), avec la commande

kubectl scale

Escalader notre déploiement

pingpong:kubectl scale deploy/pingpong --replicas 3Noter que cette autre commande fait exactement pareil:

kubectl scale deployment pingpong --replicas 3

Note: et si on avait essayé d'escalader replicaset.apps/pingpong-xxxxxxxxxx?

On pourrait! Mais le deployment le remarquerait tout de suite, et le baisserait au niveau initial.

Résilience

Le déploiement

pingpongaffiche son replica setLe replica set s'assure que le bon nombre de pods sont lancés

Que se passe-t-il en cas de disparition inattendue de pods?

- Dans une fenêtre séparée, lister les pods en continu:kubectl get pods -w

- Supprimer un podkubectl delete pod pingpong-xxxxxxxxxx-yyyyy

Et si on voulait que ça se passe différemment?

Et si on voulait lancer un conteneur "one-shot" qui ne va pas se relancer?

On pourrait utiliser

kubectl run --restart=OnFailureorkubectl run --restart=NeverCes commandes iraient déclarer des jobs ou pods au lieu de deployments.

Sous le capot,

kubectl runinvoque des "generators" pour déclarer les descriptions de ressources.On pourrait aussi écrire ces descriptions de ressources nous-mêmes (typiquement en YAML),

et les créer sur le cluster aveckubectl apply -f(comme on verra plus loin)Avec

kubectl run --schedule=..., on peut aussi lancer des cronjobs

Bon, et cet avertissement de déprécation?

Comme nous avons vu dans les diapos précédentes,

kubectl runpeut faire bien des choses.Le type exact des ressources créées n'est pas flagrant.

Pour rendre les choses plus explicites, on préfère passer par

kubectl create:kubectl create deploymentpour créer un déploiementkubectl create jobpour créer un jobkubectl create cronjobpour lancer un job à intervalle régulier

(depuis Kubernetes 1.14)

Finalement,

kubectl runne sera utilisé que pour démarrer des pods à usage unique

Divers moyens de créer des ressources

kubectl run- facile pour débuter

- versatile

kubectl create <ressource>- explicite, mais lui manque quelques fonctions

- ne peut déclarer de CronJob avant Kubernetes 1.14

- ne peut pas transmettre des arguments en ligne de commande aux déploiements

kubectl create -f foo.yamloukubectl apply -f foo.yaml- 100% des fonctions disponibles

- exige d'écrire du YAML

Afficher les logs de multiple pods

Quand on spécifie un nom de déploiement, les logs d'un seul pod sont affichés

On peut afficher les logs de plusieurs pods en ajoutant un selector

Un sélecteur est une expression logique basée sur des labels

Pour faciliter les choses, quand on lance

kubectl run monpetitnom, les objets associés ont un labelrun=monpetitnom

- Afficher la dernière ligne de log pour tout pod confondus qui a le label

run=pingpong:kubectl logs -l run=pingpong --tail 1

Suivre les logs de plusieurs pods

- Est-ce qu'on peut suivre les logs de tous nos pods

pingpong?

- Combiner les options

-land-f:kubectl logs -l run=pingpong --tail 1 -f

Note: combiner les options -l et -f est possible depuis Kubernetes 1.14!

Essayons de comprendre pourquoi ...

Suivre les logs de plusieurs pods

- Voyons ce qu'il se passe si on essaie de sortir les logs de plus de 5 pods

Escalader notre déploiement:

kubectl scale deployment pingpong --replicas=8Afficher les logs en continu:

kubectl logs -l run=pingpong --tail 1 -f

On devrait voir un message du type:

error: you are attempting to follow 8 log streams,but maximum allowed concurency is 5,use --max-log-requests to increase the limitPourquoi ne peut-on pas suivre les logs de plein de pods?

kubectlouvre une connection vers le serveur API par podPour chaque pod, le serveur API ouvre une autre connexion vers le kubelet correspondant.

S'il y a 1000 pods dans notre déploiement, cela fait 1000 connexions entrantes + 1000 connexions au serveur API.

Cela peut facilement surcharger le serveur API.

Avant la version 1.14 de K8S, il a été décidé de ne pas autoriser les multiple connexions.

A partir de 1.14, c'est autorisé, mais plafonné à 5 connexions.

(paramétrable via

--max-log-requests)Pour plus de détails sur les tenants et aboutissants, voir PR #67573

Limitations de kubectl logs

On ne voit pas quel pod envoie quelle ligne

Si les pods sont redémarrés / remplacés, le flux de log se fige.

Si de nouveaux pods arrivent, on ne verra pas leurs logs.

Pour suivre les logs de plusieur pods, il nous faut écrire un sélecteur

Certains outils externes corrigent ces limitations:

(par ex.: Stern)

kubectl logs -l ... --tail N

En exécutant cette commande dans Kubernetes 1.12, plusieurs lignes s'affichent

C'est une régression quand

--tailet-l/--selectorsont couplés.Ca affichera toujours les 10 dernières lignes de la sortie de chaque conteneur.

(au lieu du nombre de lignes spécifiées en ligne de commande)

Le problème a été résolu dans Kubernetes 1.13

Voir #70554 pour plus de détails.

Est-ce qu'on n'est pas en train de submerger 1.1.1.1?

Si on y réfléchit, c'est une bonne question!

Pourtant, pas d'inquiétude:

Le groupe de recherche APNIC a géré les adresses 1.1.1.1 et 1.0.0.1. Alors qu'elles étaient valides, tellement de gens les ont introduit dans divers systèmes, qu'ils étaient continuellement submergés par un flot de trafic polluant. L'APNIC voulait étudier cette pollution mais à chaque fois qu'ils ont essayé d'annoncer les IPs, le flot de trafic a submergé tout réseau conventionnel.

Il est tout à fait improbable que nos pings réunis puissent produire ne serait-ce qu'un modeste truc dans le NOC chez Cloudflare!

19,000 mots

On dit "qu'une image vaut mille mots".

Les 19 diapos suivantes montrent ce qu'il se passe quand on lance:

kubectl run web --image=nginx --replicas=3

Exposer des conteneurs

(automatically generated title slide)

Exposer des conteneurs

kubectl exposecrée un service pour des pods existantUn service est une adresse stable pour un (ou plusieurs) pods

Si on veut se connecter à nos pods, on doit déclarer un nouveau service

Une fois que le service est créé, CoreDNS va nous permettre d'y accéder par son nom

(i.e après avoir créé le service

hello, le nomhellova pointer quelque part)Il y a différents types de services, détaillé dans les diapos suivantes:

ClusterIP,NodePort,LoadBalancer,ExternalName

Types de service de base

ClusterIP(type par défaut)- une adresse IP virtuelle est allouée au service (dans un sous-réseau privé interne)

- cette adresse IP est accessible uniquement de l'intérieur du cluster (noeuds et pods)

- notre code peut se connecter au service par le numéro de port d'origine.

NodePort- un port est alloué pour le service (par défaut, entre 30000 et 32768)

- ce port est exposé sur toutes les nodes et quiconque peut s'y connecter

- notre code doit être modifié pour pouvoir s'y connecter

Ces types de service sont toujours disponibles.

Sous le capot: kube-proxy passe par un proxy utilisateur et un tas de règles iptables.

Autres types de service

LoadBalancer- un répartiteur de charge externe est alloué pour le service

- le répartiteur de charge est configuré en accord

(par ex.: un serviceNodePortest créé, et le répartiteur y envoit le traffic vers son port) - disponible seulement quand l'infrastructure sous-jacente fournit une sorte de "load balancer as a service"

(e.g. AWS, Azure, GCE, OpenStack...)

ExternalName- l'entrée DNS gérée par CoreDNS est juste un enregistrement

CNAME - ni port, ni adresse IP, ni rien d'autre n'est alloué

- l'entrée DNS gérée par CoreDNS est juste un enregistrement

Lancer des conteneurs avec ouverture de port

Puisque

pingn'a nulle part où se connecter, nous allons lancer quelque chose d'autreOn pourrait utiliser l'image officielle

nginx, mais...... comment distinguer un backend d'un autre!

On va plutôt passer par

jpetazzo/httpenv, un petit serveur HTTP écrit en Gojpetazzo/httpenvécoute sur le port 8888Il renvoie ses variables d'environnement au format JSON

Les variables d'environnement vont inclure

HOSTNAME, qui aura pour valeur le nom du pod(et de ce fait, elle aura une valeur différente pour chaque backend)

Créer un déploiement pour notre serveur HTTP

On pourrait lancer

kubectl run httpenv --image=jpetazzo/httpenv...Mais puisque

kubectl runest bientôt obsolète, voyons voir comment utiliserkubectl createà sa place.

- Dans une autre fenêtre, surveiller les pods (pour voir quand ils seront créés):kubectl get pods -w

Créer un déploiement pour ce serveur HTTP super-léger: server:

kubectl create deployment httpenv --image=jpetazzo/httpenvEscalader le déploiement à 10 replicas:

kubectl scale deployment httpenv --replicas=10

Exposer notre déploiement

- Nous allons déclarer un service

ClusterIPpar défaut

Exposer le port HTTP de notre serveur:

kubectl expose deployment httpenv --port 8888Rechercher quelles adresses IP ont été alloués:

kubectl get service

Services: constructions de 4e couche

On peut assigner des adresses IP aux services, mais elles restent dans la couche 4

(i.e un service n'est pas une adresse IP; c'est une IP+ protocole + port)

La raison en est l'implémentation actuelle de

kube-proxy(qui se base sur des mécanismes qui ne supportent pas la couche n°3)

Il en résulte que: vous devez indiquer le numéro de port de votre service

Lancer des services avec un (ou plusieurs) ports au hasard demandent des bidouilles

(comme passer le mode réseau au niveau hôte)

Tester notre service

- Nous allons maintenant envoyer quelques requêtes HTTP à nos pods

- Obtenir l'adresse IP qui a été allouée à notre service, sous forme de script:IP=$(kubectl get svc httpenv -o go-template --template '{{ .spec.clusterIP }}')

Envoyer quelques requêtes:

curl http://$IP:8888/Trop de lignes? Filtrer avec

jq:curl -s http://$IP:8888/ | jq .HOSTNAME

Tester notre service

- Nous allons maintenant envoyer quelques requêtes HTTP à nos pods

- Obtenir l'adresse IP qui a été allouée à notre service, sous forme de script:IP=$(kubectl get svc httpenv -o go-template --template '{{ .spec.clusterIP }}')

Envoyer quelques requêtes:

curl http://$IP:8888/Trop de lignes? Filtrer avec

jq:curl -s http://$IP:8888/ | jq .HOSTNAME

Essayez-le plusieurs fois! Nos requêtes sont réparties à travers plusieurs pods.

Si on n'a pas besoin d'un répartiteur de charge

Parfois, on voudrait accéder à nos services directement:

si on veut économiser un petit bout de latence (typiquement < 1ms)

si on a besoin de se connecter à n'importe quel port (au lieu de quelques ports fixes)

si on a besoin de communiquer sur un autre protocole qu'UDP ou TCP

si on veut décider comment répartir la charge depuis le client

...

Dans ce cas, on peut utiliser un "headless service"

Services Headless

On obtient un service headless en assignant la valeur

Noneau champclusterIP(Soit avec

--cluster-ip=None, ou via un bout de YAML)Puisqu'il n'y a pas d'adresse IP virtuelle, il n'y pas non plus de répartiteur de charge

CoreDNS va retourner les adresses IP des pods comme autant d'enregistrements

AC'est un moyen facile de recenser tous les réplicas d'un deploiement.

Services et points d'entrée

Un service dispose d'un certain nombre de "points d'entrée" (endpoint)

Chaque endpoint est une combinaison "hôte + port" qui pointe vers le service

Les points d'entrée sont maintenus et mis à jour automatiquement par Kubernetes

- Vérifier les endpoints que Kubernetes a associé au service

httpenv:kubectl describe service httpenv

Dans l'affichage, il y aura une ligne commençant par Endpoints:.

Cette ligne liste un tas d'adresses au format host:port.

Afficher les détails d'un endpoint

Dans le cas de nombreux endpoints, les commandes d'affichage tronquent la liste

kubectl get endpointsPour sortir la liste complète, on peut passer par la commande suivante:

kubectl describe endpoints httpenvkubectl get endpoints httpenv -o yamlCes commandes vont nous montrer une liste d'adresses IP

On devrait retrouver ces mêmes adresses IP dans les pods correspondants:

kubectl get pods -l app=httpenv -o wide

endpoints, pas endpoint

endpointsest la seule ressource qui ne s'écrit jamais au singulier$ kubectl get endpointerror: the server doesn't have a resource type "endpoint"C'est parce que le type lui-même est pluriel (contrairement à toutes les autres ressources)

Il n'existe aucun objet

endpoint:type Endpoints structLe type ne représente pas un seul endpoint, mais une liste d'endpoints

Exposer des services au monde extérieur

Le type par défaut (ClusterIP) ne fonctionne que pour le trafic interne

Si nous voulons accepter du trafic depuis l'extene, on devra utiliser soit:

NodePort (exposer un service sur un port TCP entre 30000 et 32768)

LoadBalancer (si notre fournisseur de cloud est compatible)

ExternalIP (passer par l'adresse IP externe d'une node)

Ingress (mécanisme spécial pour les services HTTP)

Nous détaillerons l'usage des NodePorts et Ingresses plus loin.

Shipping images with a registry

(automatically generated title slide)

Shipping images with a registry

Initially, our app was running on a single node

We could build and run in the same place

Therefore, we did not need to ship anything

Now that we want to run on a cluster, things are different

The easiest way to ship container images is to use a registry

How Docker registries work (a reminder)

What happens when we execute

docker run alpine?If the Engine needs to pull the

alpineimage, it expands it intolibrary/alpinelibrary/alpineis expanded intoindex.docker.io/library/alpineThe Engine communicates with

index.docker.ioto retrievelibrary/alpine:latestTo use something else than

index.docker.io, we specify it in the image nameExamples:

docker pull gcr.io/google-containers/alpine-with-bash:1.0docker build -t registry.mycompany.io:5000/myimage:awesome .docker push registry.mycompany.io:5000/myimage:awesome

Running DockerCoins on Kubernetes

Create one deployment for each component

(hasher, redis, rng, webui, worker)

Expose deployments that need to accept connections

(hasher, redis, rng, webui)

For redis, we can use the official redis image

For the 4 others, we need to build images and push them to some registry

Building and shipping images

There are many options!

Manually:

build locally (with

docker buildor otherwise)push to the registry

Automatically:

build and test locally

when ready, commit and push a code repository

the code repository notifies an automated build system

that system gets the code, builds it, pushes the image to the registry

Which registry do we want to use?

There are SAAS products like Docker Hub, Quay ...

Each major cloud provider has an option as well

(ACR on Azure, ECR on AWS, GCR on Google Cloud...)

There are also commercial products to run our own registry

(Docker EE, Quay...)

And open source options, too!

When picking a registry, pay attention to its build system

(when it has one)

Using images from the Docker Hub

For everyone's convenience, we took care of building DockerCoins images

We pushed these images to the DockerHub, under the dockercoins user

These images are tagged with a version number,

v0.1The full image names are therefore:

dockercoins/hasher:v0.1dockercoins/rng:v0.1dockercoins/webui:v0.1dockercoins/worker:v0.1

Setting $REGISTRY and $TAG

In the upcoming exercises and labs, we use a couple of environment variables:

$REGISTRYas a prefix to all image names$TAGas the image version tag

For example, the worker image is

$REGISTRY/worker:$TAGIf you copy-paste the commands in these exercises:

make sure that you set

$REGISTRYand$TAGfirst!For example:

export REGISTRY=dockercoins TAG=v0.1(this will expand

$REGISTRY/worker:$TAGtodockercoins/worker:v0.1)

Running our application on Kubernetes

(automatically generated title slide)

Running our application on Kubernetes

- We can now deploy our code (as well as a redis instance)

Deploy

redis:kubectl create deployment redis --image=redisDeploy everything else:

set -ufor SERVICE in hasher rng webui worker; dokubectl create deployment $SERVICE --image=$REGISTRY/$SERVICE:$TAGdone

Is this working?

After waiting for the deployment to complete, let's look at the logs!

(Hint: use

kubectl get deploy -wto watch deployment events)

- Look at some logs:kubectl logs deploy/rngkubectl logs deploy/worker

Is this working?

After waiting for the deployment to complete, let's look at the logs!

(Hint: use

kubectl get deploy -wto watch deployment events)

- Look at some logs:kubectl logs deploy/rngkubectl logs deploy/worker

🤔 rng is fine ... But not worker.

Is this working?

After waiting for the deployment to complete, let's look at the logs!

(Hint: use

kubectl get deploy -wto watch deployment events)

- Look at some logs:kubectl logs deploy/rngkubectl logs deploy/worker

🤔 rng is fine ... But not worker.

💡 Oh right! We forgot to expose.

Connecting containers together

Three deployments need to be reachable by others:

hasher,redis,rngworkerdoesn't need to be exposedwebuiwill be dealt with later

- Expose each deployment, specifying the right port:kubectl expose deployment redis --port 6379kubectl expose deployment rng --port 80kubectl expose deployment hasher --port 80

Is this working yet?

- The

workerhas an infinite loop, that retries 10 seconds after an error

Stream the worker's logs:

kubectl logs deploy/worker --follow(Give it about 10 seconds to recover)

Is this working yet?

- The

workerhas an infinite loop, that retries 10 seconds after an error

Stream the worker's logs:

kubectl logs deploy/worker --follow(Give it about 10 seconds to recover)

We should now see the worker, well, working happily.

Exposing services for external access

Now we would like to access the Web UI

We will expose it with a

NodePort(just like we did for the registry)

Create a

NodePortservice for the Web UI:kubectl expose deploy/webui --type=NodePort --port=80Check the port that was allocated:

kubectl get svc

Accessing the web UI

- We can now connect to any node, on the allocated node port, to view the web UI

- Open the web UI in your browser (http://node-ip-address:3xxxx/)

Accessing the web UI

- We can now connect to any node, on the allocated node port, to view the web UI

- Open the web UI in your browser (http://node-ip-address:3xxxx/)

Yes, this may take a little while to update. (Narrator: it was DNS.)

Accessing the web UI

- We can now connect to any node, on the allocated node port, to view the web UI

- Open the web UI in your browser (http://node-ip-address:3xxxx/)

Yes, this may take a little while to update. (Narrator: it was DNS.)

Alright, we're back to where we started, when we were running on a single node!

Accessing the API with kubectl proxy

(automatically generated title slide)

Accessing the API with kubectl proxy

The API requires us to authenticate¹

There are many authentication methods available, including:

TLS client certificates

(that's what we've used so far)HTTP basic password authentication

(from a static file; not recommended)various token mechanisms

(detailed in the documentation)

¹OK, we lied. If you don't authenticate, you are considered to

be user system:anonymous, which doesn't have any access rights by default.

Accessing the API directly

- Let's see what happens if we try to access the API directly with

curl

Retrieve the ClusterIP allocated to the

kubernetesservice:kubectl get svc kubernetesReplace the IP below and try to connect with

curl:curl -k https://10.96.0.1/

The API will tell us that user system:anonymous cannot access this path.

Authenticating to the API

If we wanted to talk to the API, we would need to:

extract our TLS key and certificate information from

~/.kube/config(the information is in PEM format, encoded in base64)

use that information to present our certificate when connecting

(for instance, with

openssl s_client -key ... -cert ... -connect ...)figure out exactly which credentials to use

(once we start juggling multiple clusters)

change that whole process if we're using another authentication method

🤔 There has to be a better way!

Using kubectl proxy for authentication

kubectl proxyruns a proxy in the foregroundThis proxy lets us access the Kubernetes API without authentication

(

kubectl proxyadds our credentials on the fly to the requests)This proxy lets us access the Kubernetes API over plain HTTP

This is a great tool to learn and experiment with the Kubernetes API

... And for serious uses as well (suitable for one-shot scripts)

For unattended use, it's better to create a service account

Trying kubectl proxy

- Let's start

kubectl proxyand then do a simple request withcurl!

Start

kubectl proxyin the background:kubectl proxy &Access the API's default route:

curl localhost:8001

- Terminate the proxy:kill %1

The output is a list of available API routes.

kubectl proxy is intended for local use

By default, the proxy listens on port 8001

(But this can be changed, or we can tell

kubectl proxyto pick a port)By default, the proxy binds to

127.0.0.1(Making it unreachable from other machines, for security reasons)

By default, the proxy only accepts connections from:

^localhost$,^127\.0\.0\.1$,^\[::1\]$This is great when running

kubectl proxylocallyNot-so-great when you want to connect to the proxy from a remote machine

Running kubectl proxy on a remote machine

If we wanted to connect to the proxy from another machine, we would need to:

bind to

INADDR_ANYinstead of127.0.0.1accept connections from any address

This is achieved with:

kubectl proxy --port=8888 --address=0.0.0.0 --accept-hosts=.*

Do not do this on a real cluster: it opens full unauthenticated access!

Security considerations

Running

kubectl proxyopenly is a huge security riskIt is slightly better to run the proxy where you need it

(and copy credentials, e.g.

~/.kube/config, to that place)It is even better to use a limited account with reduced permissions

Good to know ...

kubectl proxyalso gives access to all internal servicesSpecifically, services are exposed as such:

/api/v1/namespaces/<namespace>/services/<service>/proxyWe can use

kubectl proxyto access an internal service in a pinch(or, for non HTTP services,

kubectl port-forward)This is not very useful when running

kubectldirectly on the cluster(since we could connect to the services directly anyway)

But it is very powerful as soon as you run

kubectlfrom a remote machine

Controlling the cluster remotely

(automatically generated title slide)

Controlling the cluster remotely

All the operations that we do with

kubectlcan be done remotelyIn this section, we are going to use

kubectlfrom our local machine

Requirements

The exercises in this chapter should be done on your local machine.

kubectlis officially available on Linux, macOS, Windows(and unofficially anywhere we can build and run Go binaries)

You may skip these exercises if you are following along from:

a tablet or phone

a web-based terminal

an environment where you can't install and run new binaries

Installing kubectl

- If you already have

kubectlon your local machine, you can skip this

Note: if you are following along with a different platform (e.g. Linux on an architecture different from amd64, or with a phone or tablet), installing kubectl might be more complicated (or even impossible) so feel free to skip this section.

Testing kubectl

Check that

kubectlworks correctly(before even trying to connect to a remote cluster!)

- Ask

kubectlto show its version number:kubectl version --client

The output should look like this: